Os Costales de Mano Penalva, paisagens em trânsito

Em castelhano, costales designam sacos, normalmente utilizados para o armazenamento e transporte de alimentos. Costal, em português, faz referência às costas de uma pessoa, e a palavra é muito utilizada para referir-se aos pulverizadores agrícolas, usados nas lavouras como uma mochila. Raphia, por sua vez, é um gênero que abarca cerca de uma dezena de palmeiras, nativas de regiões tropicais africanas e, em menor número, da América Central e do Sul, cuja fibra é tradicionalmente utilizada para a confecção de esteiras, sacos, cordas, cestaria etc.

No final dos anos 1950, uma empresa italiana — a Commissionaria Vendita Macchine, Covema — começou a desenvolver ráfia sintética de polipropileno, que desde então tem sido largamente utilizada para a confecção de sacos e costales em escala industrial para o transporte de grãos, frutas, temperos, alimentos em geral (ou “secos e molhados”, no jargão do mercado) e até entulho. Pode-se dizer que o deslocamento constitui a essência desses objetos trançados. As palavras, os objetos, seus significados e usos também se entrelaçam na obra de Mano Penalva, por meio do deslocamento de seus usos e sentidos.

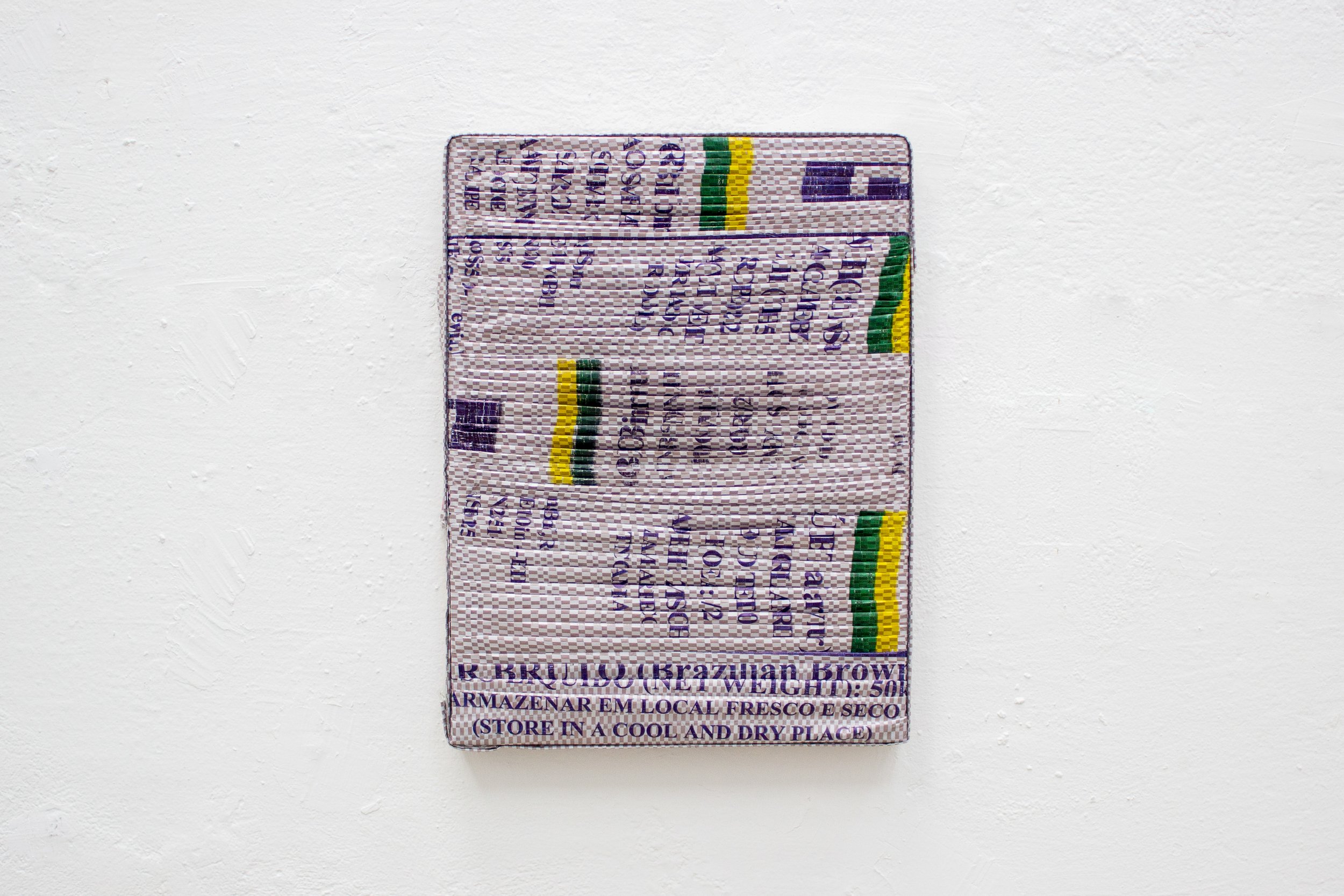

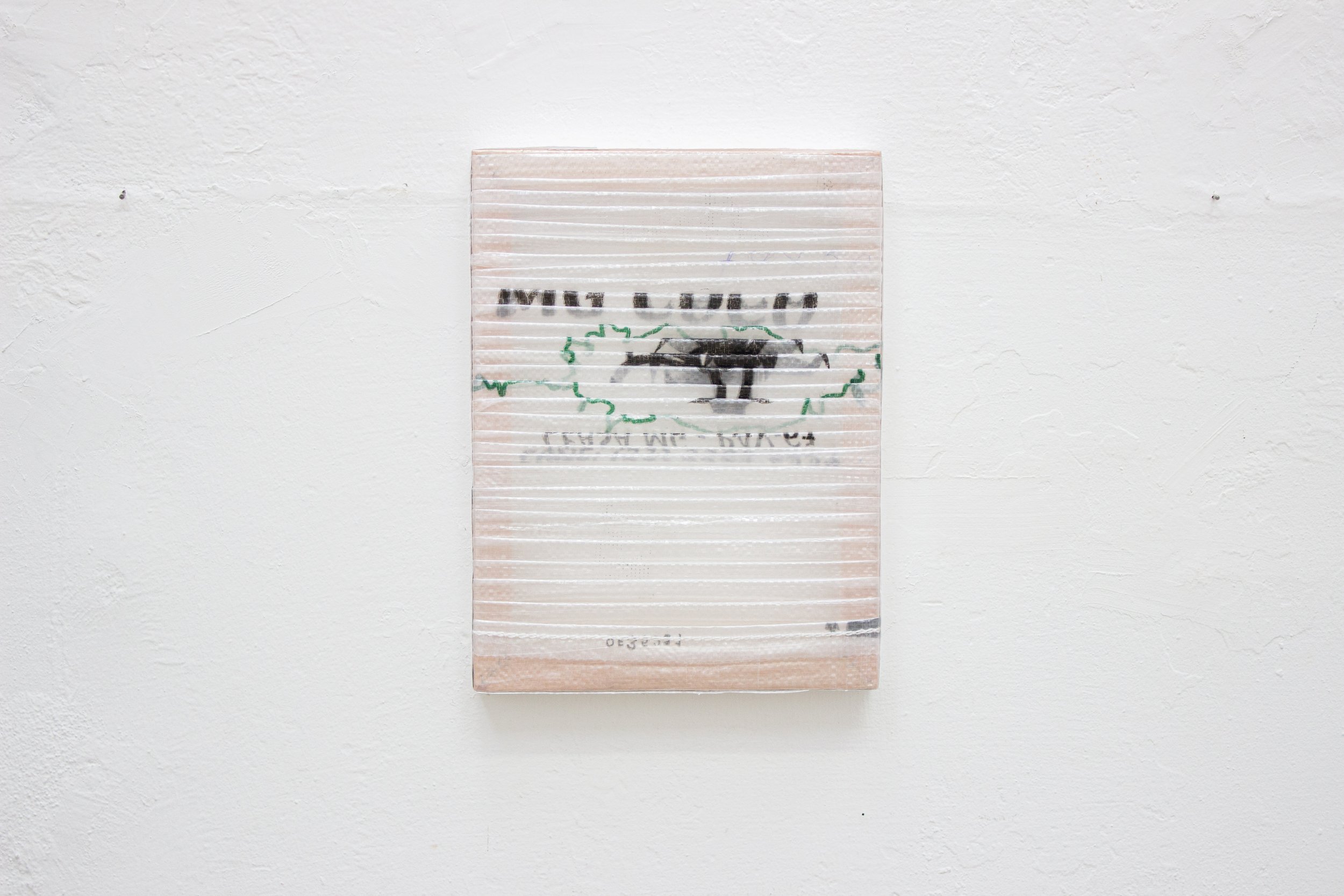

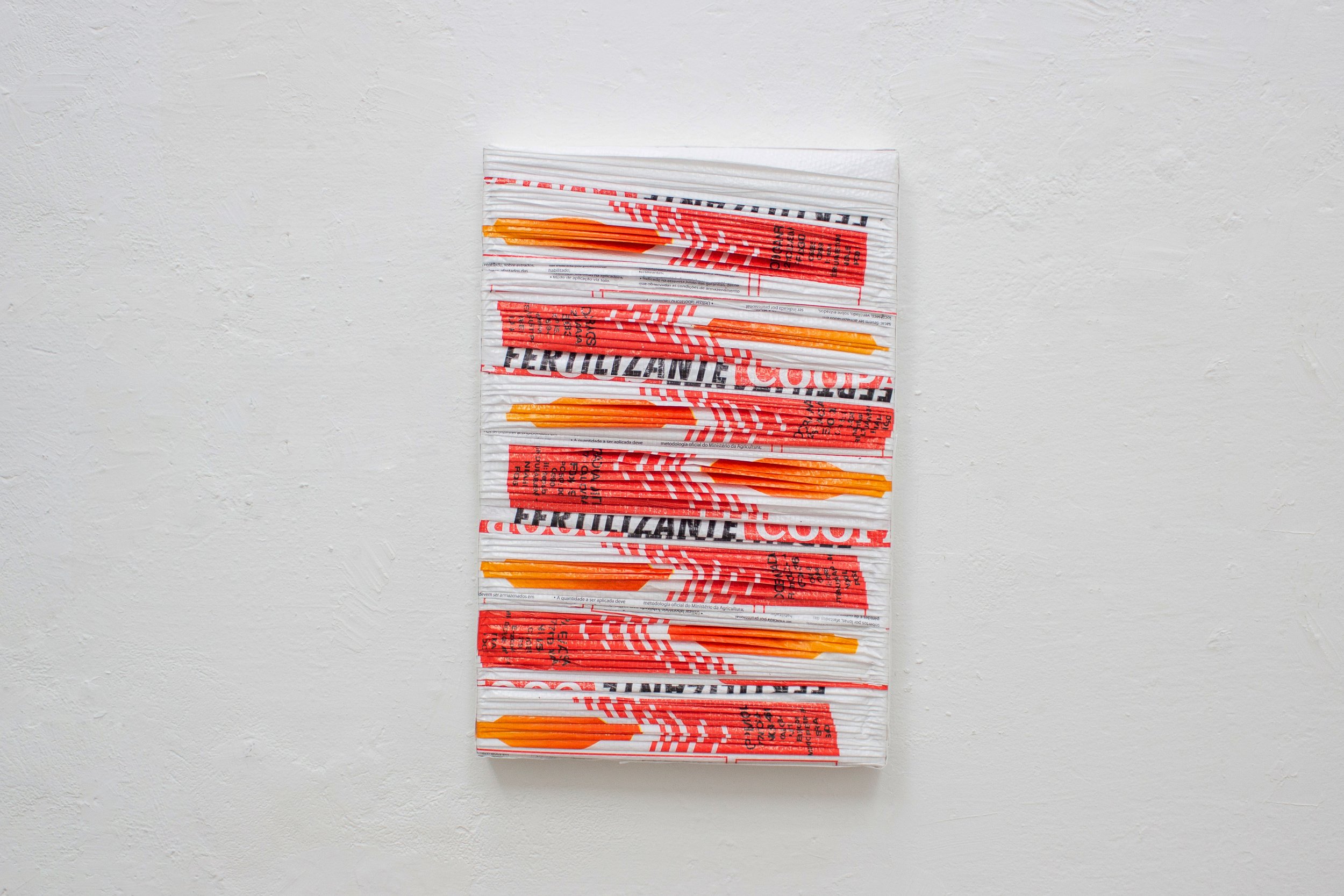

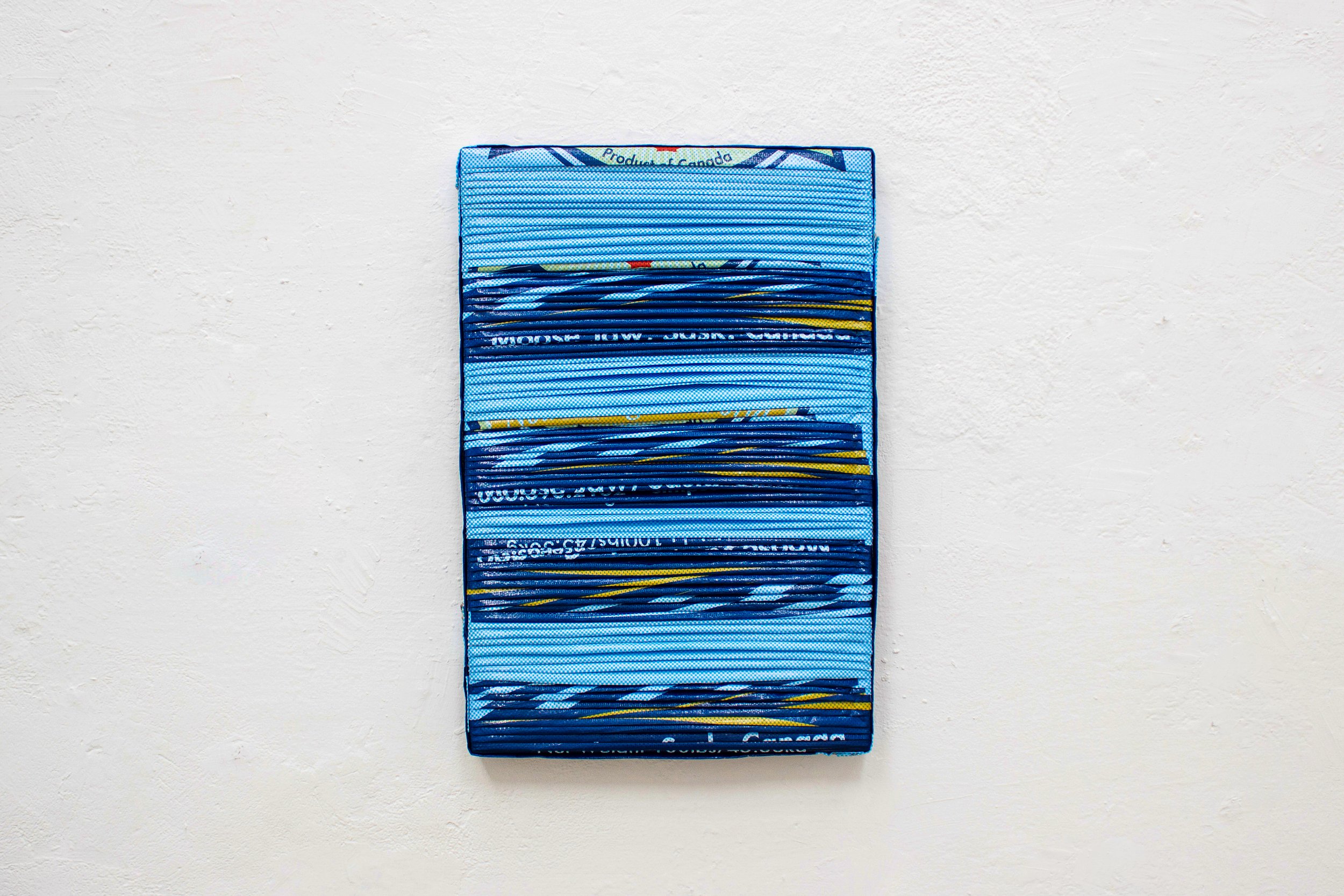

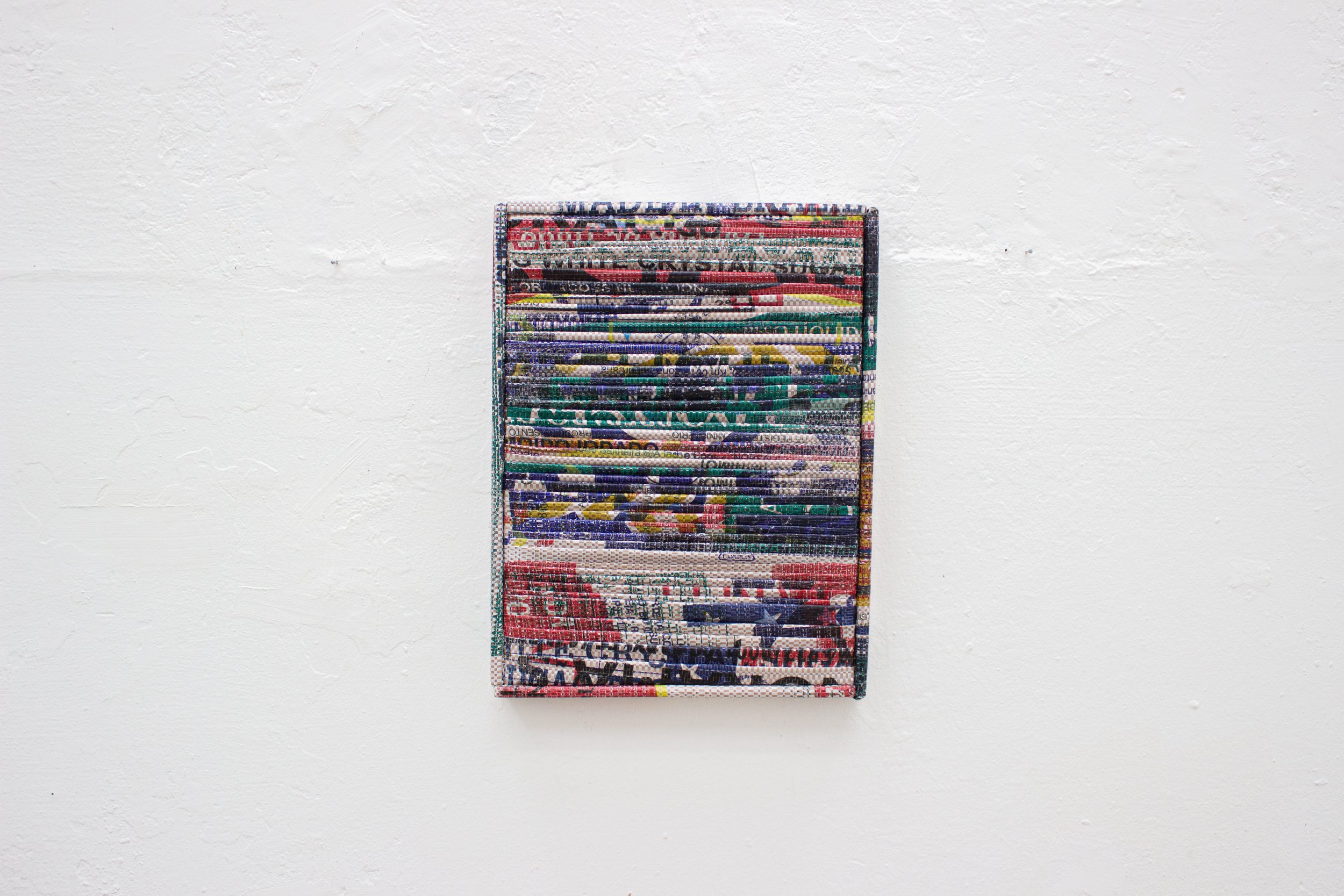

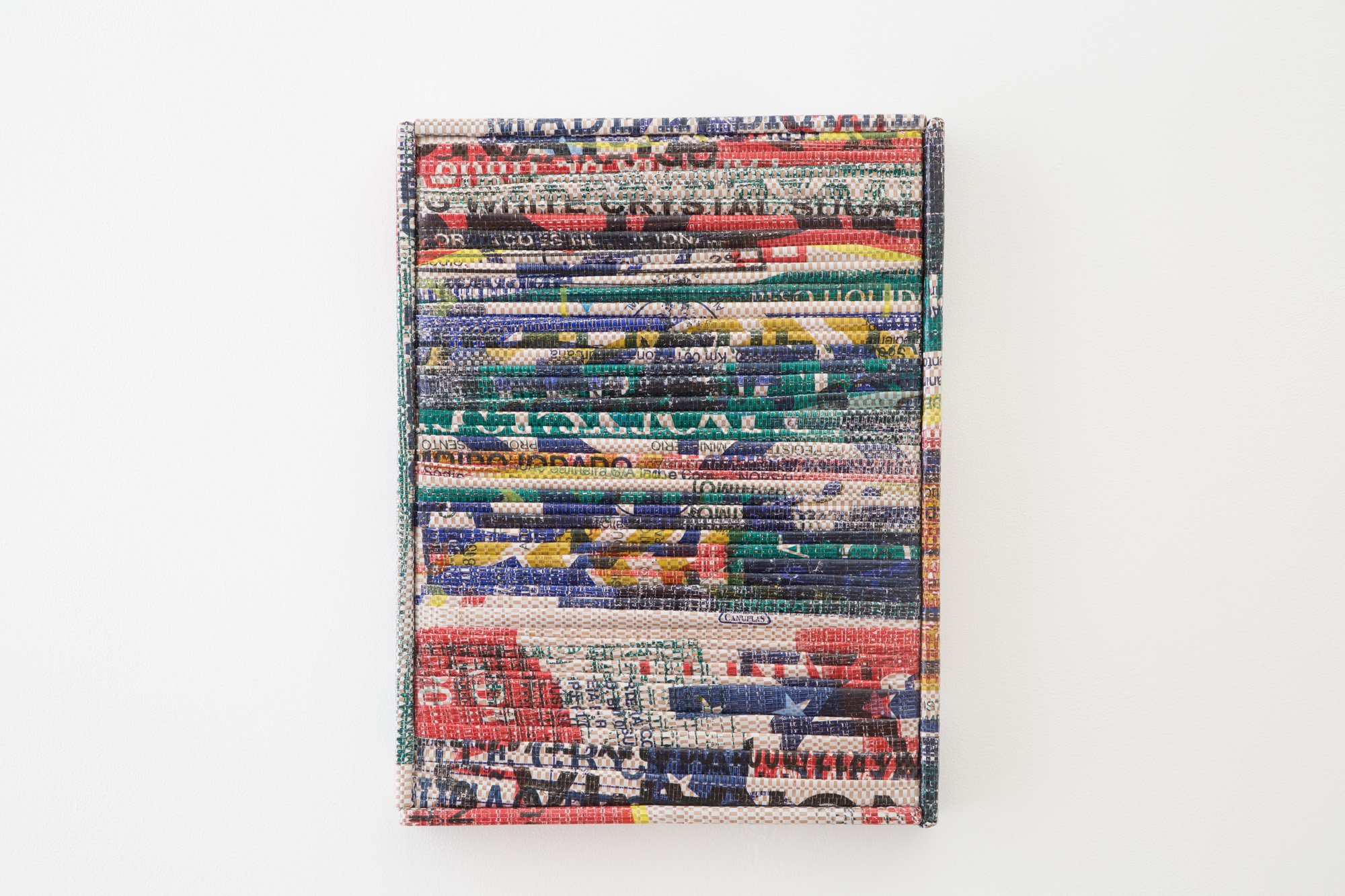

Sacos de ráfia sintética são os elementos centrais de uma série de trabalhos intitulada Origens (2016-em processo). Para encontrá-los, o artista também se desloca por várias partes, e em seguida transforma-os em pinturas de tecidos plissados e fixados num chassi. O movimento se dá em várias camadas: o trânsito global de produtos, para o qual os sacos foram feitos originalmente; o trânsito do artista, que muitas vezes precisa estar fisicamente num lugar para adquirir determinados tecidos; o deslocamento conceitual daqueles objetos, entre um sistema comercial de alimentos-commodities e o sistema (também comercial, mas altamente simbólico) da arte. A dobra da ráfia, que já não transporta nada, cria paisagens abstratas, composições autônomas.

Se levarmos em conta que os sacos transportam commodities ou, nas palavras da filósofa, física e ativista indiana Vandana Shiva, que “As corporações não plantam alimento; elas plantam lucros”, é como se Origens buscasse restituir a característica cultural dos alimentos. Ou seja, de culturas e cultivos locais que se perderam, na medida em que o trânsito global de produção e distribuição de comida foi sendo monopolizado, gerando paisagens desoladoras de monocultura, destruição e fome.

Na verdade, não se trata de uma devastação recente; a América Latina (território de origem do artista) foi, desde a sua fundação, exportadora de commodities para o fornecer o lucro e satisfazer o desejo alheio. Nas palavras do escritor uruguaio Eduardo Galeano,

Essa triste rotina dos séculos começou com o ouro e a prata, e seguiu com o açúcar, o tabaco, o guano, o salitre, o cobre, o estanho, a borracha, o cacau, a banana, o café, o petróleo... O que nos legaram esses esplendores? Nem herança nem bonança. Jardins transformados em desertos, campos abandonados, montanhas esburacadas, águas estagnadas, longas caravanas de infelizes condenados à morte precoce e palácios vazios onde deambulam os fantasmas.

Os Costales de Penalva são compostos por uma série potencialmente ilimitada de produtos, como açúcar refinado, açúcar mascavo “do Brasil”, manjericão, coco, aipim, milho, farinhas, fertilizantes. Alguns lembram campos agrícolas vistos de cima, com blocos de cor isolados, equivalentes às áreas cultivadas: amarelos, ocres, verdes, marrons, azuis e, em menor medida, cor-de-rosa e vermelhos. As “fronteiras” são evidentes como cercas, mas as formas vacilam, como se a racionalidade da divisão em lotes tivesse falhado.

Na verdade, estudos recentes vêm demonstrando aquilo que comunidades tradicionais já sabiam há muito: não há nada mais irracional do que uma monocultura que, além de funcionar como um garimpo de nutrientes exaurindo a terra, depende de insumos químicos que, ao invés de controlar “pragas”, servem para selecionar as mais resistentes, intoxicando solos, lençóis freáticos, animais e pessoas. Ainda nas palavras de Shiva, “o paradigma da agricultura industrial está enraizado na guerra: ele literalmente usa os mesmos químicos que foram antes usados para exterminar pessoas para [agora] destruir a natureza”.

Outros trabalhos da mesma série trazem fragmentos de palavras, legíveis em Fertilizante, Brown Sugar ou Coco; ilegíveis como uma cacofonia nos sacos de milho de pipoca e de açúcar refinado. Moose Jaw lembra uma marinha, com frases cortadas que parecem representar as espumas do mar. No topo, há a vaga indicação “Product of Canada”, mas não se sabe o que seria este produto. Se os sacos perderam sua função original de transporte, o texto perdeu também sua qualidade comunicativa. Restam apenas fragmentos de palavras nos costales transformados em pintura.

O artista, ao mesmo tempo em que aborda a questão das redes globais de transporte de alimentos-commodities, estabelece um diálogo com a tradição ocidental da paisagem, o segundo mais baixo gênero na hierarquia da pintura, conforme estabelecido pelas academias de belas-artes no século XVII. Em 1690, o Dicionário “universal” do francês Antoine Furetière, já trazia a conhecida definição de paisagem: “o território que se estende até onde a vista pode alcançar”. Trata-se de uma afirmação profundamente interessada, uma vez que pressupõe um espectador, sugerindo que a própria existência da natureza depende do homem e de seus olhos. A segunda definição que traz o dicionário tem um sentido cultural ainda mais explícito: “Paisagem se diz também sobre os quadros nos quais são representados algumas vistas de casas ou de campos.”

Na hierarquia dos gêneros pictóricos, o mais elevado era o da pintura histórica e/ou mitológica cujo tema, segundo a epistemologia europeia-colonial, seria o mais relevante para a representação artística, sendo a natureza um mero pano de fundo. Apesar de parecer circunscrito a um período específico da história da arte, trata-se de um paradigma cultural bastante persistente, que se reflete, por exemplo, na prática do agronegócio: a terra e seus recursos são percebidos não apenas como inertes, mas também como inesgotáveis e disponíveis para satisfazer os desejos e caprichos (de alguns) humanos. Ainda no âmbito da arte, o influente crítico francês Charles Baudelaire afirmaria numa crítica ao salão de 1859: “Se uma composição de árvores, montanhas, cursos d’água e casas, a que chamamos paisagem, é bela, não o é por si mesma, mas por mim, por minha própria graça, pela ideia ou sentimento a que a ela associo.”

As paisagens de Mano Penalva são artificiais, construídas, cuidadosamente dobradas. Sugerem que a monocultura produz campos estéreis, anti-naturais, assim como a ideia da paisagem no Ocidente, que existiria apenas por causa da “própria graça” humana. Na verdade, segundo o pensador Ailton Krenak, “Isso que chamam de natureza deveria ser a interação do nosso corpo com o entorno, em que a gente soubesse de onde vem o que comemos, para onde vai o ar que expiramos.” Ao retirar os costales de seu circuito habitual, Penalva entrelaça os vários sentidos de cultura — cultivo da terra, tradições artísticas e valores sociais —, sugerindo que a arte, essa commodity altamente valorizada e às vezes transformada em monocultura colonial, tem também o potencial de criar novas paisagens.

Abril, 2022

Notas

[1] SHIVA, Vandana. Who Really Feeds the World? The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2016, p. 24, tradução livre. No original: “Corporations do not grow food; they grow profits”.

[2] GALEANO, Eduardo. As veias abertas da América Latina. “Prefácio”. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 2010.

[3] A expressão é do pesquisador estadunidense Robert R. Schneider. Ver Government and the economy on the Amazon frontier.Washington: The World Bank, 1995, pp. 15-16.

[4] SHIVA, Vandana, op. cit., p. 12. Um exemplo é o conglomerado alemão I. G. Farben, estabelecido em 1925 entre as empresas BASF, Bayer e Hoecht, que produzia a substância Zyklon B, utilizada nas câmaras de gás nazistas.

[5] Disponível em https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k50614b.image.

[6] Apud LICHTENSTEIN, Jacqueline (org.). A pintura: textos essenciais. Vol. 10: os gêneros pictóricos. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2008, p. 124, grifos meus.

[7] KRENAK, Ailton. A vida não é útil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2020, p. 74.

//en

Mano Penalva's Costales, landscapes in transit

In Castilian, costales designate bags, normally used for the storage and transportation of food. “Costal”, in Portuguese, refers to a person’s back, and the word is often used to refer to agricultural sprayers, which are used in the fields like a backpack. Raphia, in its turn, is a genus that includes about a dozen palm trees, native to tropical regions of Africa and, to a lesser extent, Central and South America, which fiber is traditionally used for making mats, bags, ropes, basketry, etc.

In the late 1950s, an Italian company — Commissionaria Vendita Macchine, Covema — started to develop synthetic polypropylene raffia, which since then has been widely used for the manufacture of bags and costales on an industrial scale for the transport of grains, fruits, spices, food in general (or “dry and wet goods”, in the jargon of the market) and even rubble. One could say that displacement is the essence of these woven objects. Words, objects, their meanings and uses are also intertwined in Mano Penalva's work, through the displacement of their uses and meanings.

Synthetic raffia bags are the central elements of a series of works entitled Origins (2016—in-progress). To find them, the artist also moves through several fields, and then transforms them into pleated fabric paintings attached to a chassis. The movement is multi-layered: the global transit of goods, for which the bags were originally made; the transit of the artist, who often needs to be physically in a place to acquire certain fabrics; the conceptual displacement of those objects, between a commercial commodity food system and the (also commercial, but highly symbolic) art system. The raffia fold, which no longer carries anything, creates abstract landscapes, autonomous compositions.

If we take into account that the bags carry commodities or, in the words of Indian philosopher, physicist, and activist Vandana Shiva, that “Corporations do not grow food; they grow profits”,[1] it is as if Origins seeks to restore the cultural characteristic of food — that is, of local cultures and crops that have been lost as the global transit of food production and distribution has been monopolized, creating desolate landscapes of monoculture, destruction, and hunger.

In fact, this is not a recent devastation; Latin America (the artist's home territory) has been, since its foundation, an exporter of commodities to supply profit and satisfy the desire of others. In the words of the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano,

This sad routine of centuries began with gold and silver, and continued with sugar, tobacco, guano, saltpeter, copper, tin, rubber, cocoa, bananas, coffee, oil… What did these splendors bequeath us? Neither inheritance nor bonanza. Gardens turned into deserts, abandoned fields, hollowed-out mountains, stagnant waters, long caravans of unfortunates condemned to early death and empty palaces where the ghosts roam.[2]

Penalva’s Costales are made up of a potentially limitless array of products, such as refined sugar, brown sugar “from Brazil”, basil, coconut, manioc, corn, flour, fertilizers. Some resemble agricultural fields seen from above, with isolated blocks of color equivalent to cultivated areas: yellows, ochres, greens, browns, blues, and to a lesser extent, pinks and reds. The “borders” are evident as fences, but the forms hesitate, as if the rationality of the division into lots has failed.

In fact, recent studies have been demonstrating what traditional communities have long known: there is nothing more irrational than a monoculture that, besides functioning as a nutrient mining [3] that exhausts the land, depends on chemical inputs that, instead of controlling “pests”, serve to select the most resistant ones, intoxicating soils, water tables, animals, and people. Also in Shiva's words, “the paradigm of industrial agriculture is rooted in war: it very literally uses the same chemicals that were once used to exterminate people to [now] destroy nature”.[4]

Other works in the same series bring fragments of words, legible in Fertilizer, Brown Sugar or Coconut; and illegible as a cacophony in the bags of popcorn and caster sugar. Moose Jaw resembles a marine, with cut phrases that seem to represent the foams of the sea. At the top, there is the vague indication “Product of Canada”, but it is not known what this product would be. If the bags have lost their original function of transportation, the text has also lost its communicative quality. All that remains are fragments of words in the costales transformed into paintings.

The artist, while addressing the issue of global food-commodities transportation networks, also establishes a dialogue with the Western tradition of landscape, the second lowest genre in the hierarchy of painting as established by the academies of fine arts in the 17th century. In 1690, the “universal” Dictionary by the Frenchman Antoine Furetière already had the well-known definition of landscape: “the territory that extends as far as the eye can see”.[5] The second definition the dictionary brings has an even more explicit cultural meaning: “Landscape is also stated about the pictures in which some views of houses or fields are represented”.

In the hierarchy of pictorial genres, the highest was historical and/or mythological painting, whose theme, according to European-colonial epistemology, would be the most relevant for artistic representation, nature being a mere background. Although it seems circumscribed to a specific period in the history of art, it is a very persistent cultural paradigm, which is reflected, for example, in the practice of agribusiness: the earth and its resources are perceived not only as inert, but also as inexhaustible and available to satisfy (some) human desires and whims. Still in the realm of art, the influential French critic Charles Baudelaire would state in a review of the 1859 salon: “If a composition of trees, mountains, waterways, and houses, which we call landscape, is beautiful, it is so not by itself, but by me, by my own grace, by the idea or feeling with which I associate it”.[6]

Mano Penalva’s landscapes are artificial, constructed, carefully folded. They suggest that monoculture produces sterile, unnatural fields, just like the idea of landscape in the West, which would exist only because of humans’ “own grace”. In fact, according to the thinker Ailton Krenak, “This thing they call nature should be the interaction of our body with its surroundings, where we would know where what we eat comes from, where the air we breathe out goes”.[7] By taking the costales out of their usual circuit, Penalva interweaves the various meanings of culture — cultivation of the land, artistic traditions, and social values — suggesting that art, this highly valued commodity sometimes transformed into a colonial monoculture, also has the potential to create new landscapes.

Notes

[1] SHIVA, Vandana. Who Really Feeds the World? The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2016, p. 24, tradução livre. No original: “Corporations do not grow food; they grow profits”.

[2] GALEANO, Eduardo. As veias abertas da América Latina. “Prefácio”. Porto Alegre: L&PM, 2010.

[3] The expression was coined by US researcher Robert R. Schneider. See Government and the economy on the Amazon frontier. Washington: The World Bank, 1995, pp. 15-16.

[4] SHIVA, Vandana, op. cit. p. 12. An example is the German conglomerate I. G. Farben. G. Farben, established in 1925 between the companies BASF, Bayer and Hoecht, which produced the substance Zyklon B, used in Nazi gas chambers.

[5] Available in https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k50614b.image

[6] Apud LICHTENSTEIN, Jacqueline (org.). A pintura: textos essenciais. Vol. 10: os gêneros pictóricos. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2008, p. 124, my italics. Free translation from the Portuguese.

[7] KRENAK, Ailton. A vida não é útil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2020, p. 74. Free translation from Portuguese.